Tom Watson

(Published in Fall 2025 issue of Whitetails Unlimited magazine)Tom Watson

The term “survival” gets tossed around quite a bit in outdoor chat circles, most often centering around procedures that evolved from many of the extreme behind-the-lines enemy-evading tactics straight out of the U.S. Air Force survival manual. Hollywood’s contributions, as well as television reality “survival” shows, each portray unrealistic images from the other end of the definition spectrum.

For today’s outdoor enthusiast, emergency scenarios are quite less dramatic, but potentially just as life-threatening. Having even a basic sense of survival self-reliance can mean the difference between being rescued – and being recovered!

Hunting has one of the lowest incidents of accidents among at least a dozen popular outdoor activities. However, falls involving tree stands are the number one cause of such accidents among deer hunters (3,000-4,000/year). Other common, non-gun related) hunting accidents include sprained ankles, cuts, and hypothermia. A little less than ten percent of all hunting-related accidents result in a fatality.

So why would having basic, hands-on knowledge of survival processes and skills be of any significant importance to the average, responsible deer hunter?

Because things happen!

A bad move using a tree stand, an ankle-wrenching stumble while tracking a deer, a damaged or unusable vital piece of gear (clothing/shelter/equipment) or becoming disoriented as daylight wanes are some of the many ways your comfort and security from the elements can be compromised on even the most routine weekend hunt. While spending a night ill-prepared for the elements, or nursing an unexpected injury may not seem initially life-threatening, they can certainly affect your comfort level and can potentially lead to a more critical situation.

Most experts agree that the best piece of “survival” gear is right between your ears – your brain! Developing and maintaining a Positive Mental Attitude (PMA) can help you draw upon whatever self-reliant skills you may need to survive. It’s not only what you carry in your survival kit that matters – it’s knowing the importance of potential resources around you, how to identify their potential uses, – and to understand why a certain task is critical to your survival.

Back in the 80s, the Alaska Marine Safety Institute developed a seven-step process designed to help stranded commercial fishermen as well as US Coast Guard personnel survive in the harsh North Pacific coastal environment. That program has since been expanded to develop survival steps applicable to any outdoor environment and situation – from hikers to paddlers to back-country hunters. These Seven Steps To Survival, when executed in sequence and repeated as needed, can help you focus on dealing with many potentially life-threatening ‘survival’ situations.

Here are those seven steps, to be followed in order, and why each step is vital to your overall survival and eventual rescue:

1. Know you are in trouble – Realize and accept that you are in a serious situation. This is no time to succumb to denial or hide behind your ego, the sooner you accept that you are in danger, the sooner you can start using your PMA and engage the seven step process. Many survival instructors refer to this as one’s “Oh S—t!” moment.

2. Inventory your situation – First and foremost, check for any injuries; then check others. Check for any cuts, bruise or other injuries that need immediate attention or that should be monitored later.

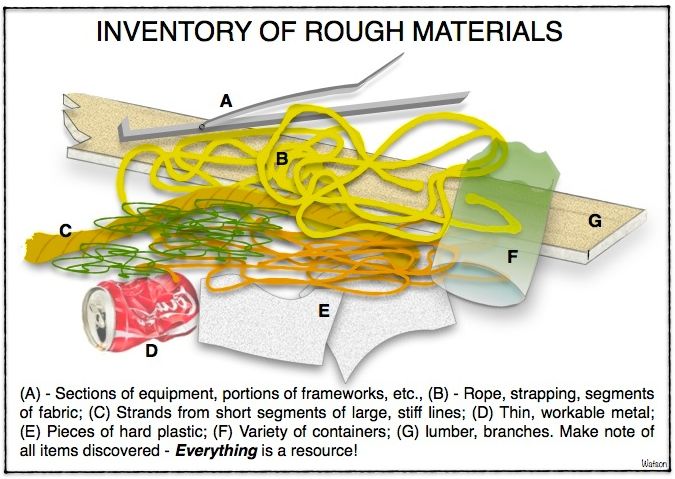

Check your gear to see what equipment is no longer functional – or that you would need but don’t have. Perhaps a tent or tarp was trashed by the wind, maybe your insulated jacket was destroyed or blew away, Knowing what you have for gear (for either initial use or jerry-rigged for other uses) will force you to improvise.

It’s also important to check your surroundings for both potential resources and any inherent dangers within the immediate environment. Dismiss nothing, make a mental record of everything you tally on a survey of your surroundings (potential shelter, fire materials, dangers from trees, overhangs, other hazards, etc.,).

3. Shelter – The main purpose of a shelter is to protect you from the elements (the effects of wind, rain/snow), and to keep you as warm and dry as possible. All these are methods to ward off “exposure” or hypothermia as it is now called. Keeping warm means insulating your body from losing heat – that’s “why” you are creating a shelter. Knowing that, even crawling inside a huge pile of dried field grass can be a way of creating a layer of insulation between you and the elements. Knowing why you should do something can often provide you with ‘how’ to go about it should your main process not be possible to achieve.

Here’s a critical point of priority: Most dramatic scenarios of a survival situations show victims building a fire as their first task. If you have several members in your party, assign a few of them to that process. More importantly, however, is to create adequate shelters for everyone. If you start out dry and while attempting to build a fire, it starts to rain, you have no place to retreat to – and are now getting wet and cold. Build even a modest shelter before you attempt a fire!

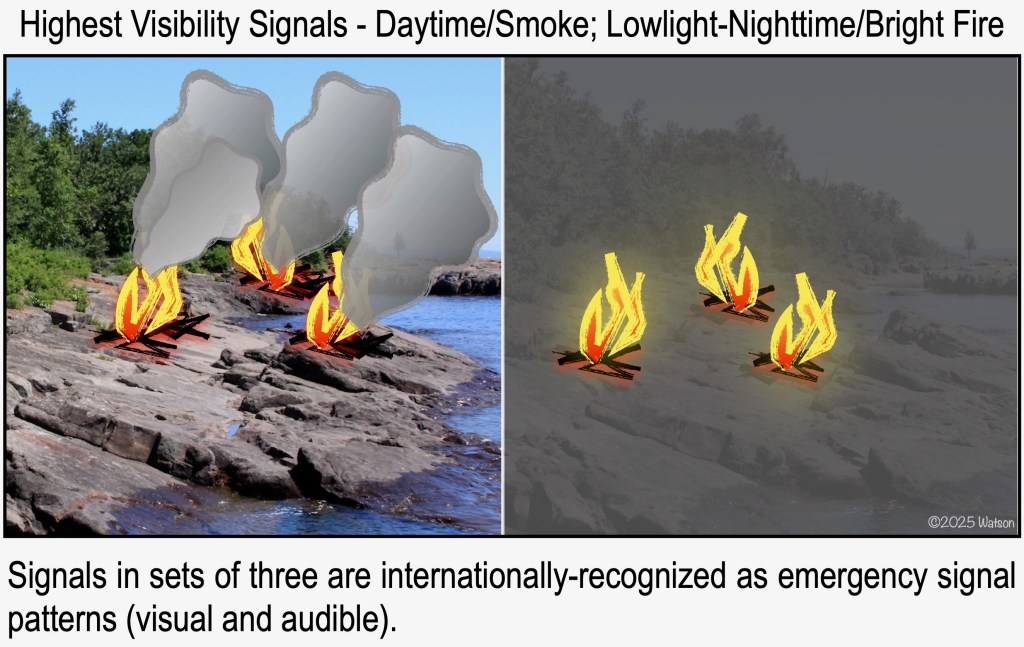

4, Signals – Anything that draws attention to your location is a signal, and the best signals are those in highest contrast, visually with their surroundings, or audibly above the din present around you. A set of three visual/audible sounds (fires, whistles, gun shots) is internationally recognized as a signal for help. During hunting season, distinguishing a signal from a series of shots from an area being hunted may not prompt anyone to assume it’s a call for help.

Knowing who might hear those reports – a game warden on patrol in the field, your own hunting party – can help you direct/time your signals accordingly. Also, smoke signals (dense, dye-colored flumes) are the best signaling devices by day; bright hand-held or aerial flares, or signal bonfires work best at night.

Every member of your hunting party should carry a whistle, a high decibel, noise-producing tool that will send out a sound signal. You can establish coded whistling sequences to signal back and forth, too. Most importantly, you can blow the three-note distress call for hours on end, and much longer and louder than by yelling and straining your throat.

Water – Staying hydrated is critical in any outdoor situation. You should be drinking water before you feel thirsty. Lack of water can lead to disorientation of thought, impaired physical motion and other signs that, if not addressed, can lead to a survival situation down the trail. lt’s also recommended to drink as much water at a time as you can rather than ration it out as you want to stay alert and as hydrated as possible while you seek out water sources.

Eat / Food – Food is fuel, it stokes our internal furnace to provide heat and power. There are several axioms used in the outdoor environment that are pretty much the ‘words of wisdom’ regarding eating in an emergency situation:

- If you don’t know what it is, don’t eat it!

- Just because it’s edible doesn’t mean it’s going to taste good!

- If you don’t have a lot of water, don’t eat much food (water is needed to help metabolize food).

Here’s a good survival food trick a Coastguardsman taught me – pack a tiny bottle of hot sauce (Tabasco) in your emergency survival kit. It can help mask the unpleasant taste of most ‘wild’ foods.

Play! – While the survival situation is extremely serious, it’s still important to maintain a positive mental attitude, to stay alert and rely on your own skills to endure whatever hardship you are experiencing. In a group situation, “play” can be simply having a firewood contest or other camp tasks, simple diversions to keep anquished thoughts in check.

You can run through the seven steps over and over again as your situation changes (hopefully improving with each sequence).

Even a casual evening hunt can turn into a challenging overnight ordeal if something goes wrong. While some of the seven steps are designed to help mitigate long-term, multi-day emergency scenarios, learning basic emergency self-reliant skills may help you deal with most any survival situations, one step at a time.

Leave a comment