One of the lighter, but important aspects of being self reliant in the outdoors is the level to which you can bring your kitchen skills to the campfire. Whether it’s a casual car-camp weekend or a backcountry bivouac or spike camp, there’s no reason why you can’t enjoy some of the cooking creations you enjoy at home.

While it’s part of the Rites of Passage to roast a few ‘dogs’ over the campfire or heat the beans right from the can, imagine what a steaming hot biscuit or a baked potato could add to the day’s menu.

I thought I’d offer a few basic baking tips I’ve found helpful as I began to expand my campfire cook- ing skills. No matter what was on my campfire test kitchen list, “test” was and remains the key word – test the process at home before you plan to add it to your outdoor menu.

I’ve prepared many a ‘camping’ dish in my fire ring on my deck or in my BBQ kettle. I could use the briquets or charcoal for the heat source, containing and somewhat controlling the temperature while I fine- tuned the baking process. It paid off in spades on many prepared dishes I assumed would turn out fine, only to realize that what had worked in the kitchen didn’t always translate well when cooked outdoors on glowing embers.

Baking was always the challenge; controlling the temperature and judging the overall cooking time was always a challenge, especially with varying and often unstable temperatures. I did learn a few tricks to pass on – ones that pretty much apply to most all the baking options one might use in the field.

Preparing the bed of coals – First and foremost you need to prepare a uniform bed of coals using either burning hardwood (long-lasting, hotter coals of ash, hickory, some maples but not cottonwood or conifers) or commercial BBQ fuels (briquets/charcoal). Once your bed is established and stabilized

(you can add a few pieces of fuel as needed) you are ready to start baking right in your campfire ring.

Use the right baking pan.

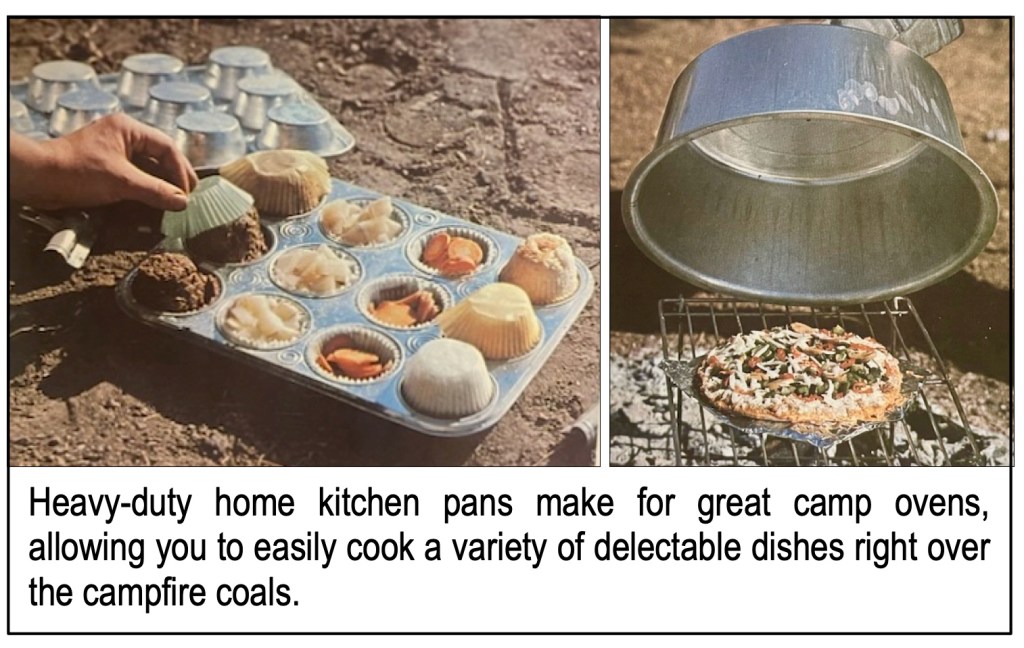

Lightweight, one- use aluminum pan molds found in grocery stores work fine, sometimes better when doubled because of their thin, pressed sheets. Heavier-duty metal pans will usually last longer and distribute heat more evenly, performing better overall. Using large muffin tins, one atop the other to form micro ovens that can be used for buns, re-heating pre-cooked foods, mini-cakes and other single portion fare.

Dutch ovens – a “must have” utensil regardless of your cooking style, the Dutch oven is ideal (if not ‘required’) for baking biscuits and cakes. There’s even a reliable formula for maintaining proper heat distribution so you don’t end up with charred bot- toms and soggy dough middles: Use one briquet for every inch of the pot’s diameter plus three more for placing on the top lid. Arrange the bottom coals to span the entire surface of the bottom of the Dutch oven using three less than the diameter of the kettle. For example, a ten inch kettle requires 13 embers on top, and seven on the bottom. Test- ing at home will help you tweak those numbers based on the kind of Dutch oven you have, the preparation at hand and the sustainable heat from the coals.

One of my favorite breakfasts in camp was always bacon/sausage and eggs and a hearty serving of fried potatoes and onions on the side. It often took longer to cook the raw potatoes slices than it did to cook everything else. Having a partially-baked spud to slice up made the entire morning camp meal come together sooner.

An easy trick to have a potato ready for final/complete cooking was to start baking it the night be- fore in the dwindling heat of your evening campfire. Simply wrap the potato in a few layers of foil – just as you would if you baked it at home – and nestle those wrapped spuds along the edge of the fir ring and cover with the dying embers raked from the center of the fire. The residual heat of the stones and embers slow cook the spuds while you sleep. At breakfast time, the spuds are uncov- ered, the foil peeled off and any charred sections of skin removed. The bulk of the mostly done potato is ready to be sliced and cooked as fast as any of the other ingredients.

It’s always a good idea to try out new techniques and test or break in new gear before you intend to apply it in the field. Cooking up new meals is no different – and creat- ing your own test kitchen in the backyard can save you some belly-rumbling disasters in camp.

2

Leave a comment